It is my great pleasure to be teaching an introduction to landscape ecology seminar for students enrolled in Jefferson University’s MS in Sustainable Design program. The seminar is being coordinated with an Ecological Design studio led by program director Rob Fleming and Max Zahniser, a green building expert and thought leader in regenerative design (Max and I worked together years ago at WRT). The students (who hail from architectural and interior design backgrounds) are using a stakeholder-driven, integrated design process to generate regenerative and resilient design solutions for a Philadelphia neighborhood. In doing so, they will apply concepts from the seminar to develop ecological landscape designs at the site and neighborhood scales.

Which raises the question…what is ecological landscape design? Let’s start by considering the discipline of landscape ecology. Richard Forman (often called the father of landscape ecology, at least in the United States) and Michael Godron defined a landscape as “a heterogeneous land area composed of a cluster of interacting ecosystems that are repeated in similar form throughout” and landscape ecology as the “study of the structure, function, and change” in a landscape. Structure refers to the spatial relationships among landscape elements, including patches, corridors, edges, and matrix, which together form the landscape mosaic. Function refers to the flows of energy, mineral nutrients, and species among the landscape elements. Change refers to the ecological dynamics of the landscape mosaic over time. Unlike classic ecological science, which focused on undisturbed natural ecosystems, landscape ecology addresses the role of humans in creating and affecting landscape patterns and process; it is an applied discipline that can be used to inform design and management of the landscape to achieve sustainable outcomes.

Ecological landscape design draws on the principles of landscape ecology to create landscapes that evolve and sustain themselves over time with limited human intervention. It draws on the discipline of ecological restoration, whose goal is to renew or restore a degraded, damaged, or destroyed ecosystem, by establishing new ecosystems whose functioning provide benefits for people and other species. In Principles of Ecological Landscape Design, Travis Beck describes an ecological landscape as one that:

…knits itself into the biosphere so that it is both sustained by natural processes and sustains life within its boundaries and beyond. It is not a duplicate of wild nature…but a complex system modeled after nature…It is flexible and adaptable and continually adjusts its patterns as conditions change and events unfold.”

Ecological landscape design is, of course, not a new concept; precedents include, among others, the work of Danish-American landscape architect Jens Jensen (credited with creating the Prairie School of landscape architecture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries), and Ian McHarg, whose landmark book Design with Nature (1969) espoused an ecological approach to design at the regional scale. Perhaps what is different is the urgency of the moment – despite McHarg’s clarion call to reverse Western civilization’s legacy of environmental despoliation, the last 50 years have seen continued loss of biodiversity, degradation of natural resources, and the emergence of climate change as an existential crisis. With these threats has come increasing awareness of the role of landscapes and the ecosystem services they provide, such as climate regulation, flood mitigation, and carbon sequestration, as a vital part of the response. At the site scale, the Sustainable SITES Initiative is a rating system for sustainable land design and development that measures project performance across a range of factors, from site context to water, soil, and vegetation; materials selection; human health and well-being; and sustainable operations and maintenance. SITES is based on the premise that “any project holds the potential to protect, improve, and regenerate the natural benefits and services provided by healthy ecosystems.”

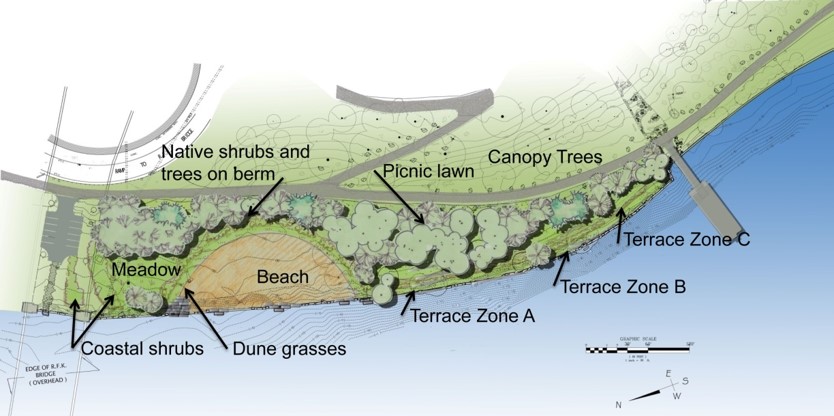

The Randall’s Island living shoreline in New York City is an example of an ecological landscape design. Located in a dynamic environment subject to flooding and sea level rise, the project replaced a crumbling seawall with a “cusp beach” (mimicking a naturally occurring coastal formation) and “sacrificial berm” deliberately designed to erode during the winter to feed the beach, along with a series of terraces planted with native vegetation. The result is a more resilient landscape that will accommodate flooding and adapt to sea level rise over time while providing improved habitat and public access to the water’s edge.

In closing, let’s return to the Ecological Design studio project. The study area is part of the highly urbanized Greater Philadelphia landscape near the confluence of two creek systems and the Delaware River. Largely consisting of filled land that replaced freshwater tidal marsh, the area is subject to flooding that will be exacerbated by projected sea level rise. Residents have a strong attachment to the place and its natural setting. A recently completed planning process with extensive community engagement identified opportunities for development that brings additional amenities, services, and jobs while conserving open space and mitigating flood risk. In their proposals at the neighborhood and site scales, the students will apply ecological landscape design principles with the goal of creating a sustainable landscape whose structure, function, and adaptability to change model natural processes and provide ecosystem services for residents. In many ways, the project is the microcosm of the larger challenges facing the design and planning professions in what has been termed the Anthropocene – the age of humans, climate change, and mass species extinction. Can the principles of ecological landscape design be scaled up from site and neighborhood to create sustainable, resilient landscapes at the city and regional scales and beyond? Can these landscapes integrate physical, biological, and cultural patterns and processes in ways that benefit both people and natural ecosystems while unleashing potential and evolving capability to resolve seemingly intractable problems like climate change? And what new approaches, research, and tools do designers and planners need to achieve this paradigm shift?

References

Beck, Travis. Principles of Ecological Landscape Design. Island Press, 2013.

Fleming, Kelly. “The Evolving Practice of Ecological Landscape Design.” American Society of Landscape Architects, The Dirt, August 2017. https://thefield.asla.org/2017/08/01/the-evolving-practice-of-ecological-landscape-design/

Forman, Richard T.T and Michael Godron. Landscape Ecology. John Wiley & Sons, 1986.

Green, Jared. “Lovefest: Landscape Architects and Restoration Ecologists.” American Society of Landscape Architects, The Dirt, October 2013. https://dirt.asla.org/2013/10/14/lovefest-landscape-architects-and-ecologists/

Green Business Certification Inc., Sustainable SITES Initiative. SITES v2 Reference Guide for Sustainable Land Design and Development. 2014. https://www.usgbc.org/resources/sites-rating-system-and-scorecard