In one of my current roles as a Senior Advisor to Econsult Solutions, Inc. (ESI) I had the opportunity to attend a presentation on ESI Thoughtlab’s global research initiative, Building a Hyperconnected City. This project surveyed 100 cities across the globe about their use of advanced technologies, data, and analytics, along with returns on smart city investments. ESI economists used the survey to develop a “Hyperconnected Cities Index” ranking cities by their progress in four key areas (pillars) of excellence: technology, data and analytics, cybersecurity, and citizen engagement.

What is a Hyperconnected City and Who Does it Serve?

My first reaction to the presentation was to ask: What is a hyperconnected city and how does it differ from a smart city? ESI’s response was that “hyperconnected cities go beyond current smart city solutions to unlock the full economic, social, environmental, and business value from technology. They have, or are in the process of, interlinking government, business, and academia, as well as residents. By aligning urban assets and stakeholders, cities are fueling a virtuous cycle of economic and social gains.” As a planner, this prompted a further question: how can planning help leverage the potential of smart and hyperconnected cities to realize community goals and values?

The answer to the above question starts with a basic premise: smart city technology is not an end in itself, but a tool to serve people. While this may seem obvious, it has not always been the case. Back in 2015 Boyd Cohen identified three generations of the Smart Cities movement. In Smart Cities 1.0 (technology driven), technology providers encourage cities to adopt smart city solutions without really understanding implications for their residents. In Smart Cities 2.0 (technology enabled, city led), forward-looking mayors and administrators determine the role of technological innovation in shaping the city’s future. Smart Cities 3.0 (which Cohen believed to be the future of the movement) involves “citizen co-creation” to determine how technology can best serve community needs.

Citizen Engagement

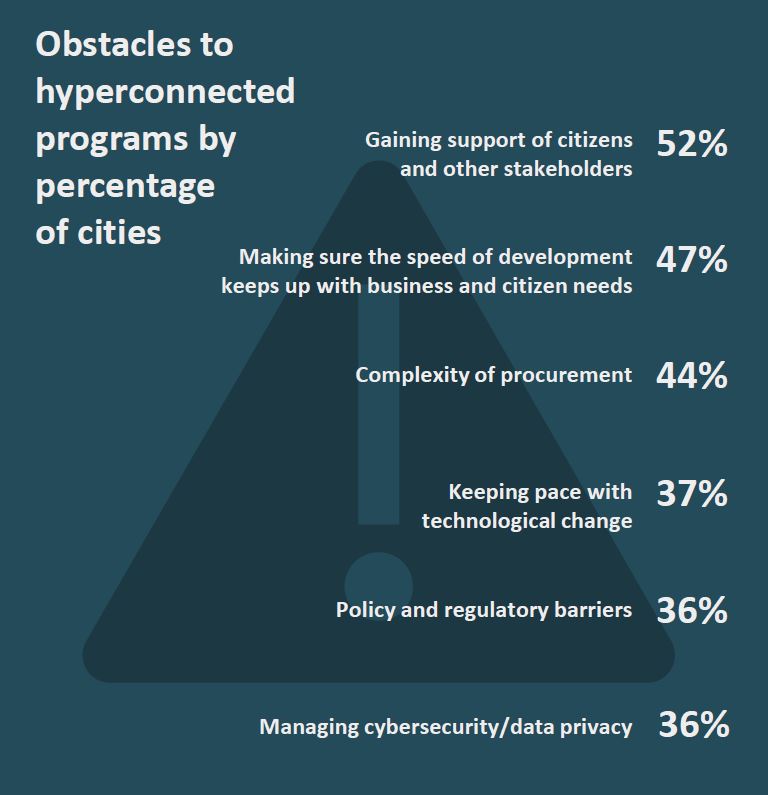

Returning to Building a Hyperconnected City, the cities surveyed by ESI identified obstacles to implementing hyperconnected programs. The number one obstacle – identified by 67% of North American cities and 52% of cities worldwide – was “gaining the support of citizens and other stakeholders.” Contributing factors include concerns regarding data privacy and cybersecurity (related to data control by technology companies, a characteristic of Cohen’s Smart Cities 1.0), the need for communication to inform citizens of smart city initiatives (reflecting the city-led model of Smart Cities 2.0), and the need to engage all segments of the community in the initiatives (analogous to citizen co-creation in Smart Cities 3.0).

As noted, ESI developed a Hyperconnected Index ranking cities in four pillars of excellence. The connected citizen pillarmeasures how well cities engage with their key stakeholders and the methods they use to communicate and interact. Four U.S. cities – Detroit (ranked #2), New York, Houston, and Chicago – ranked in the top 10 for this pillar. By contrast, two U.S. cities ranked in the top 10 for use of digital technologies, one ranked in the top 10 for data and analytics, and none for cybersecurity. (Not surprisingly, Singapore ranked #1 in three of the four categories: technology, data and analytics, and connected citizens.)

Planning the Hyperconnected City

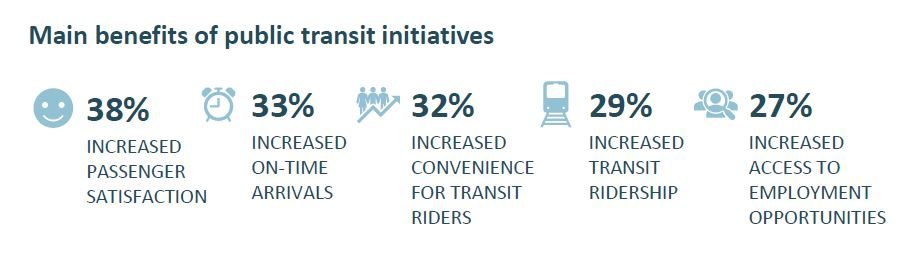

As part of the survey, ESI asked city leaders to estimate returns on investment from hyperconnected projects. Eight areas of performance rose to the top: public transit, traffic management, water, waste collection and the environment, energy and electricity, public safety, and public health.

These are important applications in which technology, data, and analytics are generating environmental, economic, and social value. It strikes me, however, that they only hint at the potential of what is being called the Fourth Industrial Revolution, in which new technologies such as artificial intelligence, automation, and biotechnology – for better or worse – are fusing the biological, digital, and physical worlds, in ways that are disrupting industries, economies, and society. Successfully navigating this next stage of development will require leveraging the transformative power of emerging technologies to achieve sustainable, resilient, and equitable outcomes, while dealing with serious downsides such as rising inequality, privacy and cybersecurity threats, and replacement of human by machine labor. Moreover, in this era of climate change, natural resource depletion, and mass species extinction, it is imperative to find a path forward that regenerates both human and natural ecosystems.

Which brings us back to the role of planning in leveraging the potential of smart and hyperconnected cities to realize community goals and values. This starts with inclusive community engagement in all phases of the planning process, from long-range visioning and goal setting through plan development and implementation, to determine how technology can best serve people and the public interest. Questions to ask and answer include: How can advanced technology, data, and analytics support community values and aspirations as expressed in the vision statement? How will plan strategies for community systems such as land use, transportation, economic development, and green infrastructure drive technological investments? What policies, standards, and incentives are needed to maximize the benefits and minimize the negative impacts of disruptive new technologies? How will the hyperconnected city serve and create opportunity for all members of the community, including historically disadvantaged populations, in an open, inclusive manner?

Inclusive engagement means bringing together citizens and other sectors, interests, and stakeholders – government, business, academic institutions, etc. – in a dialogue about the role of technology in the community’s future. Realizing the potential of the hyperconnected city in the context of rapid change, uncertainty, and disruption caused by emerging technologies will require shifts in organizational and community cultures to foster innovation and experimentation; cross-sectoral collaboration and new ways of working together; new adaptive management and monitoring systems; and more – all to fulfill community goals and values through the strategic use of technology.

The ESI study concludes by stating: “As we enter the Fourth Industrial Revolution, becoming a smart city is no longer enough. To unlock the full economic, social, environmental, and business value from technology, cities need to morph into hyperconnected urban centers.”Much more work needs to be done, but this suggests to me that hyperconnected cities could become the next generation of sustainable, resilient, and equitable cities – Smart Cities 4.0 – by fully harnessing the power of technology to serve people and community.

References

Cohen, Boyd. “The 3 Generations of Smart Cities: inside the development of the technology driven city.” Fast Company, August 2015. https://www.fastcompany.com/3047795/the-3-generations-of-smart-cities

ESI Thoughtlab. Building a Hyperconnected City: A Global Research Initiative. 2019. https://econsultsolutions.com/esi-thoughtlab/hyperconnected-city/

Schwab, Klaus. The Fourth Industrial Revolution. World Economic Forum, 2016.