Climate change, inequality, political divisiveness – the litany of social ills goes on and on, making it difficult to feel anything but pessimistic about the future. As an aging baby boomer, one thing that gives me hope for the future is the promise I see in the young to take on the challenges that have grown exponentially during my generation’s life span.

This past academic year I had the pleasure of teaching students in three graduate programs at two universities: the Urban Studies and Planning program at the University of Maryland (fall semester 2023) and the MS in Sustainable Design (MSD) and Master of Urban Design (MUD) at Thomas Jefferson University (spring semester 2024). At the University of Maryland (UMD), I taught a course called Recent Developments in Urban Studies: The Comprehensive Plan. At Thomas Jefferson University (TJU), I taught Ecological Systems for Resilient Cities for the MSD program and a Masters Research Studio (in which ten students completed theses) for the MUD program. The courses had a mix of international and domestic students with diverse professional backgrounds and life experiences, but a common commitment to making the world a better place.

In the fall semester UMD course, students learned about the comprehensive planning process, the substantive contents of leading contemporary plans, and effective plan implementation, with sustainability, resilience, equity, and system thinking as key themes. The Comprehensive Plan: Sustainable, Resilient, and Equitable Communities for the 21st Century (Routledge 2022), the book I wrote with Rocky Piro, was the course textbook. The students also worked on a real-world project: a green infrastructure plan for the Lancaster Metro Region in Pennsylvania, with the Lancaster County and City Planning Departments serving as clients.

MS in Sustainable Design (MSD) Students, Thomas Jefferson University

In the spring semester Ecological Systems course at TJU, MSD students learned about principles of landscape ecology (structure, function, and change) and ecological landscape design (Travis Beck’s Principles of Ecological Landscape Design, published by Island Press in 2013, was the course textbook). The course was coordinated with a Sustainable Design studio, taught by Professor Saglinda Roberts, in which students applied what they learned to a plan for the Ridge Avenue corridor in Philadelphia. In the Research Studio, MUD students addressed a range of thesis topics, from uncovering the unanticipated impacts of electric vehicles to revolutionizing big box stores to addressing the lack of equitable and accessible green spaces (all three using Philadelphia as a case study). Several students used generative design (a form of artificial intelligence) to optimize design performance, for example in a mixed-use development site in Guangzhou, China.

While there’s much that could be covered, I’ll share just three highlights from the body of work produced by the students across the two semesters. First is the integration of green infrastructure at the landscape scale (the original definition of the term by the Florida Greenways Commission, back in the 1980s) with green stormwater infrastructure at the site or local scale (the more recent definition developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). This is evident in the green infrastructure plan developed by the UMD students for Lancaster County’s central growth area, which builds on Greenscapes (the county’s green infrastructure plan) and GreenIt! Lancaster, the city’s plan that focuses on green stormwater infrastructure.

Rendering of urban farm with native plantings (Sanskruti Patel)

Second is what I would call “sustainable design thinking” (an alternative to conventional planning and design thinking) in the TJU students’ work on the Ridge Avenue Corridor Plan. A hallmark of the MSD program, this holistic approach was evident in how students with undergraduate degrees in architecture and interior design absorbed and applied unfamiliar landscape ecology and ecological design concepts to the plan. Examples include “big picture” goals (green stormwater management, native habitat creation and restoration, community engagement with nature, etc.); beautifully rendered site plans and perspectives; and detailed plant lists emphasizing biodiversity, pollinator-friendly species, and other ecosystem services.

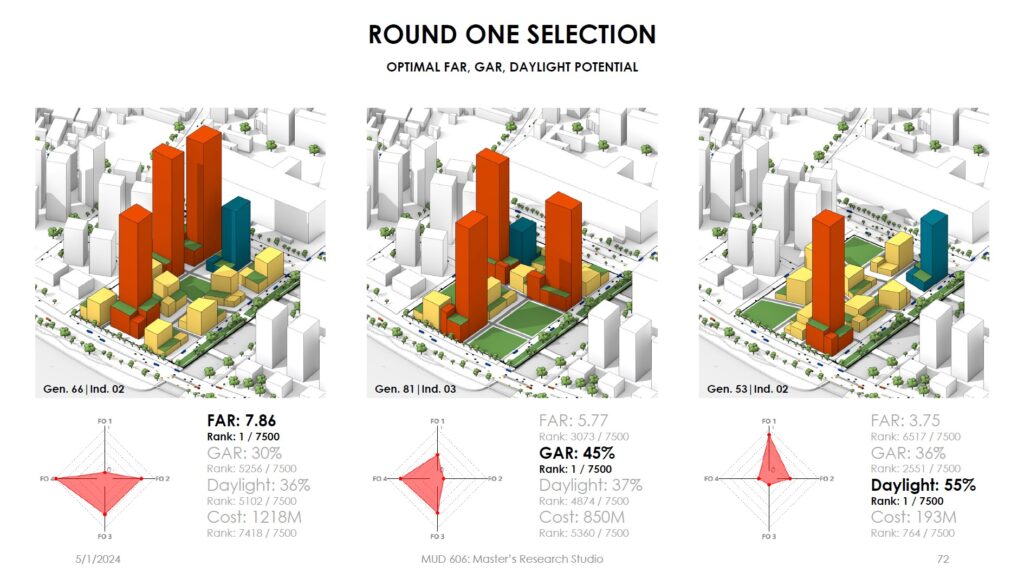

Third (and particularly timely given the recent surge of interest in artificial intelligence) is the application by MUD students of computational software (Rhino, Grasshopper, Wallacei, etc.) and multi-objective evolutionary algorithms to the design process to generate and evaluate the performance of literally thousands of alternatives. One student, for example, applied this approach to analyze multiple building typologies in a San Francisco neighborhood for their potential to address the city’s housing crisis based on five performance metrics: number and size of dwelling units, floor area ratio, economic feasibility/affordability, open space access, and solar energy potential. This work demonstrates the potential of artificial intelligence to bring unprecedented levels of power and predictive analytical capability to the design process. At the same time, it raises a host of questions for future urban designers and planners to sort out, for example: What is the role of humans and the proper balance between humans and machines in the design process? Will artificial intelligence preempt or empower community and stakeholder engagement in the process? Can computers generate design solutions that are functional, sustainable, AND beautiful?

Generative design process, Guangzhou, China case study (Geoffrey Little)

My courses were taken by a tiny subset of the students at universities across the nation and globe who will inherit the big challenges of the 21st century, which continue to grow in urgency, scale, and impact. Integrated, transdisciplinary approaches are needed to address these challenges – for example, landscape-scale conservation, ecological restoration, and incorporation of natural systems into the built environment at all levels of practice. With all their promise and perils, technological tools unimaginable when I was a graduate student can be used in this effort – for example, the emerging concept called the Internet of Nature uses digital technology to represent, describe, and manage urban ecosystems and green spaces in cities.1

Will the next generation of planners and designers succeed where previous generations too often failed, in an increasingly divisive society? Only time will tell, but I am encouraged by the promise shown by my students. Which brings me back to the theme I started with, which is to celebrate the next generation of planners and designers. So let’s conclude by wishing them the best of luck, both in their individual careers and collective impact in promoting a sustainable, resilient, and equitable future!

1Galle, Nadinè J., Sophie A. Nitoslawski, and Francesco Pilla. “The Internet of Nature: How taking nature online can shape urban ecosystems,” The Anthropocene Review 2019, Vol. 6(3), pp. 279–287