Systems thinking is a holistic approach to analysis that focuses on the way that a system’s constituent parts interrelate and how systems work over time and within the context of larger systems. The systems thinking approach contrasts with traditional analysis, which studies systems by breaking them down into their separate elements. Ben Lutkevich, Tech Target

Planners like to say we are systems thinkers. Given its comprehensive scope and crosscutting characteristics, planning would seem to lend itself to holistic (as opposed to piecemeal or linear) approaches compared to narrower, more specialized professions. But do planners really apply systems thinking in a rigorous way in planning practice?

To help answer that question, let’s compare planning to architecture, one of its sister professions. Architects design buildings (examples of systems comprising interconnected subsystems) and are systems thinkers by virtue of professional training and experience. Good architects work with other professionals to optimize building performance in the design of exterior and interior features and subsystems such as heating, cooling, lighting, water, and waste. In doing so, they strive to achieve outcomes such as energy efficiency, occupant comfort, functionality, and aesthetics.

Planners work at larger scales than architects, with the community (city or town) as a core area of practice. Similar to a building, a community is a system comprising multiple subsystems (for example, physical systems like transportation and infrastructure; social systems like schools and community services; and natural systems like hydrology and vegetation). These subsystems, in turn, contain “second level” subsystems; for example, roads, sidewalks, bicycle facilities, transit service, and the like for a transportation system. Compared to buildings, which are smaller in scale and have defined boundaries, communities are orders-of-magnitude greater in their level of complexity.

As the official planning document guiding future growth, preservation, and change in a local governmental jurisdiction, the comprehensive plan is the logical vehicle to determine the extent to which planners are applying systems thinking at the communitywide scale. The traditional 20th century comprehensive plan contained separate elements – land use, transportation, housing, and so forth – with limited recognition of how they interconnect. Increasingly, contemporary comprehensive plans are organized around overarching themes that cut across topical elements – implicitly a form of systems thinking in its recognition of interconnections between community systems such as land use and transportation. However, when Rocky Piro and I reviewed dozens of comprehensive plans for our book The Comprehensive Plan: Sustainable, Resilient, and Equitable 21st Century Communities, we found no evidence that planners are explicitly applying systems thinking concepts in practice. Which leads to a follow-up to our first question: Given the immense complexity of communities compared to smaller-scale, more defined systems, how can planners apply systems thinking to improve the process, substance, and outcomes of comprehensive plans?

System Characteristics

In her classic book, Thinking in Systems: A Primer (published posthumously in 2008), Donella Meadows defines a system as “an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organized in a way that achieves something” (i.e., it has a function or purpose). The purpose of a transportation system, for example, is to move people, vehicles, and goods (with varying degrees of emphasis). Simply stated, the purpose of a community is to provide habitat for people. According to Meadows, basic characteristics of systems include:

- Systems have stocks and flows of material and information. In a transportation system, for example, stocks are physical infrastructure components such as streets, roads, and rail lines. Flows are the people, vehicles, and goods that move through the system.

- System stocks and flows are regulated by feedback loops. Feedback loops are circular (as opposed to linear) pathways formed by an effect returning to its cause and generating either more or less of the same effect. Balancing feedback loops maintain system stability by resisting changes beyond set thresholds (for example, a thermostat that regulates room temperature). A community scale example might be to monitor municipal water use and enact conservation measures when desired levels are exceeded. Reinforcing feedback loops amplify change, either in a desirable or undesirable direction. An example might be the use of public funding to attract private investment to a targeted revitalization area, thus generating momentum for additional investment.

- Systems operate within a hierarchy of larger and smaller systems. A community is a geographically defined system that is both the aggregate of smaller systems (subareas, neighborhoods, and districts) and an element of a larger system (region), which in turn is part of larger systems (megaregion and beyond). Collectively, these different scales form a hierarchy. Functional systems such as transportation connect different levels of the system hierarchy.

- Leverage points are places in the system where a small change could lead to a large shift in behavior. Effectively applying systems thinking in practice involves using leverage points to shift system behavior to bring about desired change. Meadows identifies 12 places to intervene in a system, from least to most impactful (Figure 1). An example familiar to planners is to change system rules (incentives, punishments, constraints), which she ranks fifth most impactful. More powerful still are to change system goals or paradigms (the mindset out of which the system arises). An example of the latter might be to change the paradigm for a transportation system from emphasizing movement of vehicles and goods to emphasizing mobility and access for people.

Figure 1. Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System (Meadows 2008)

| 12. Numbers (least impactful) | 6. Information Flows |

| 11. Buffers | 5. Rules |

| 10. Stock-and-Flow Structures | 4. Self-Organization |

| 9. Delays | 3. Goals |

| 8. Balancing Feedback Loops | 2. Paradigms |

| 7. Reinforcing Feedback Loops | 1. Transcending Paradigms (most impactful) |

Albany 2030 Comprehensive Plan: An Example of Systems Thinking

Albany 2030 is the first comprehensive plan in the long and colorful history of Albany, NY, which was first established as a Dutch trading post in the early 17th century. Adopted in 2012, Albany 2030 is an example of intentional application of a systems approach to a comprehensive plan. (Full disclosure: the plan was prepared by my former firm WRT as lead consultant.) This approach had two basic premises. First, the comprehensive plan is organized around eight interrelated systems (for example, community form, transportation, and housing and neighborhoods). Second, the effectiveness of comprehensive plan implementation depends upon aligning and optimizing the performance of these systems through strategies and actions aimed at realizing the Albany 2030 vision and goals.

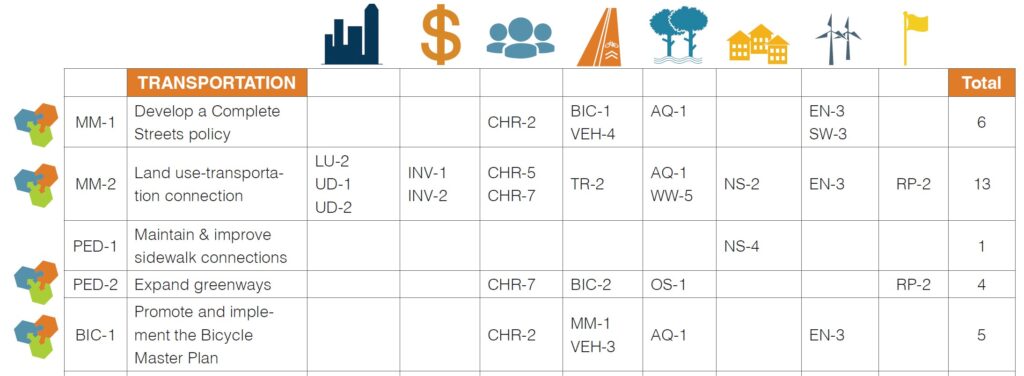

Albany 2030 used a four-step process to prioritize projects for implementation:

- Identify community priorities through public input (including a participatory budget exercise).

- Identify and quantify system overlaps (strategies and actions connecting two or more systems) using a systems interrelationship matrix (Figure 2).

- Identify strategies and actions targeting four keys to achieving the Albany 2030 vision statement (referred to as leverage points in the plan).

- Synthesize the results of steps 1 through 3 to develop strategies and actions into priority implementation projects.

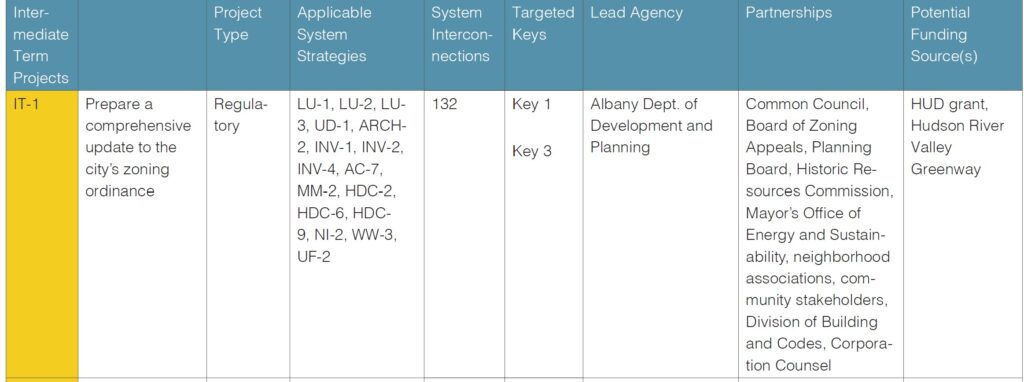

Using this process, the plan identified eight short-term, nine intermediate-term, and three long-term projects, along with eight ongoing programs, as priorities for implementation (Figure 3). Each project or program “bundled” multiple strategies and actions from across the eight comprehensive plan systems.

April 2022 marked the tenth anniversary of Albany 2030’s adoption, raising the question as to how successful the city has been in implementing the plan. Implementation success can be measured in two ways. First, did the city carry out the priorities identified in the plan? Second, did these efforts achieve the outcomes envisioned in the plan?

With regard to the first measure, the two highest priority projects based on the number of system interconnections were to 1) prepare a comprehensive update to the city’s zoning ordinance and 2) create a capital improvement program, both of which were implemented. According to the city’s website, the new Unified Sustainable Development Ordinance “better aligns with the city’s priorities and promotes sustainable development.” An Albany 2030 Comprehensive Plan Cross-Walk was prepared to identify ordinance provisions that implement strategies and actions across the eight comprehensive plan systems. A capital improvement program has been incorporated into the city’s annual budget. The 2023 budget includes narrative text on departmental accomplishments and goals, many of which support directions set by the Albany 2030 Comprehensive Plan.

To assess the second measure, let’s take a brief look at outcomes related to the four keys to achieving the Albany 2030 vision statement. Albany has established a new Department of Neighborhood and Community Services and initiated a variety of projects and programs to strengthen neighborhoods and improve quality of life (key 1). According to its 2022 annual report, Capitalize Albany (the city’s economic development arm) has catalyzed more than $2 billion in new investment citywide through business, real estate, and strategic development (keys 2 and 3). Led by the city’s Sustainability Office, Albany has implemented a range of actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, promote renewable energy use, and become a green community (key 4).

Applying Systems Thinking to Planning Practice

Based on an admittedly cursory review, Albany has experienced a considerable degree of success in implementing the Albany 2030 Comprehensive Plan. While it is not clear how many of the projects and programs identified in the plan have been carried out, the highest priorities have been accomplished and the four keys to achieving the vision statement have moved forward. The extent to which this progress can be attributed to the comprehensive plan and its systems approach to implementation is a question that cannot be answered without more in-depth research and evaluation. The initial returns are nonetheless promising, which brings us back to our original question: how can planners apply systems thinking in a rigorous way to the comprehensive plan and other aspects of planning practice? To which I would add a second question: how can the results be demonstrated through successful implementation?

I propose five ways in which planners, individually and collectively as a profession, can develop answers to these two questions. They are:

1. Gain a basic understanding of system principles (stocks, flows, feedback loops, etc.). Donella Meadows’ Thinking in Systems: A Primer is a good place to start. This book is required reading for sustainable design students at Thomas Jefferson University (where I teach a course on ecological landscape design), but I haven’t seen it on reading lists for planning courses.

2. Identify real-world examples of systems, their distinguishing characteristics, and how they behave. For example, a natural ecosystem like a forest or lake is a biological community of organisms and their physical environment. Natural ecosystems are distinguished by a spatial structure and relationships between elements; flows of energy, nutrients, and species; and the dynamics of change over time.

3. Assess how different systems interact and influence each other. A relatively simple example familiar to planners is the land use-transportation connection, which they address through policies like transit-oriented development. In urban environments multiple systems interact in complex and sometimes messy ways. Consider, for example, how transit-oriented development can impact and be impacted by socioeconomic systems, and the potential for unintended side effects like gentrification.

4. Apply lessons learned to planning practice as an alternative to traditional, piecemeal approaches. Examples of applying system principles during the planning process might include:

- Characterize community systems in terms of their purpose, behavior, components, and interactions (inventory and analysis).

- Develop goals articulating how the purpose, behavior, and interactions of different systems must change to realize the community’s desired future (vision and goals).

- Develop strategies and actions that target leverage points to catalyze desired system change (implementation).

5. Evaluate implementation outcomes to determine the effectiveness of systems approaches in achieving plan goals and policies. Implementation is arguably the weakest aspect of planning practice, and there is a dearth of research on what it takes to successfully implement a comprehensive or other type of plan. Establishing clear procedures and measures to monitor progress in carrying out the plan is essential both to realizing desired outcomes and to building a body of research on the effectiveness of systems and other approaches to implementation.

Conclusion

Acknowledging that there’s a lot more that could be written on such an ambitious topic, I’ll offer a few closing thoughts. First, even the best attempts to model systems at the community scale are crude, imperfect representations of a complex reality. Effective models provide a way to conceptualize how systems work and interact as an alternative to conventional mechanistic, piecemeal thinking. Doing so can help avoid what Meadows calls “system traps” – for example, reinforcing feedback loops that reward the successful, thus increasing socioeconomic inequality – and uncover opportunities to address the root causes of undesirable or harmful system behavior. Second, as a product of “command-and-control” 20th century approaches, established implementation practices are ill-suited to address the complexity and accelerating uncertainty of 21st century systems. In Cities That Think like Planets: Complexity, Resilience, and Innovation in Hybrid Ecosystems, Marina Alberti calls for urban planners to move away from the “myths” of stability and optimality towards increasing diversity and adaptation capacity, reconfiguring problem definitions and solutions, and designing policies and strategies to be robust under divergent but plausible futures (Alberti 2016). Finally, successful systems thinking is more than the literal application to practice of concepts and principles like those described in this article. It involves changing mindsets, ways of observing the world, and approaches to conceptualizing problems and identifying solutions. The best planners go beyond conventional analyses to explore underlying conditions, causes, and effects; see the interconnections between seemingly disparate issues; and are creative and innovative in developing goals, strategies, and tactics that can effectuate meaningful change. They are, indeed, systems thinkers after all.

The future can’t be predicted, but it can be envisioned and brought lovingly into being. Systems can’t be controlled, but they can be designed and redesigned…We can’t impose our will on a system. We can listen to what the system tells us, and discover how its properties and our values can work together to bring forth something much better than could ever be produced by our will alone. Meadows, pp. 169-170

References

Albany, NY. Albany 2030 Comprehensive Plan, 2012.

Alberti, Marina. Cities That Think Like Planets: Complexity, Resilience, and Innovation in Hybrid Ecosystems. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016.

Meadows, Donella H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Edited by Diana Wright, Sustainability Institute. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2008.